Cats

It had been exactly a year since the separation from my wife of twenty years. I had moved into a small apartment in Midtown. It was a big change from the leafy suburbs of River Park, but much more suited to the lifestyle I was now leading: partying, going to concerts, and walking most everywhere, including to work and back. It was a cool little fourplex. I eventually secured one of the coveted off-street parking spots, and I tried to spruce up the back area where I’d have my nightly after-work beer with a fire pit, some chairs, and a small herb garden.

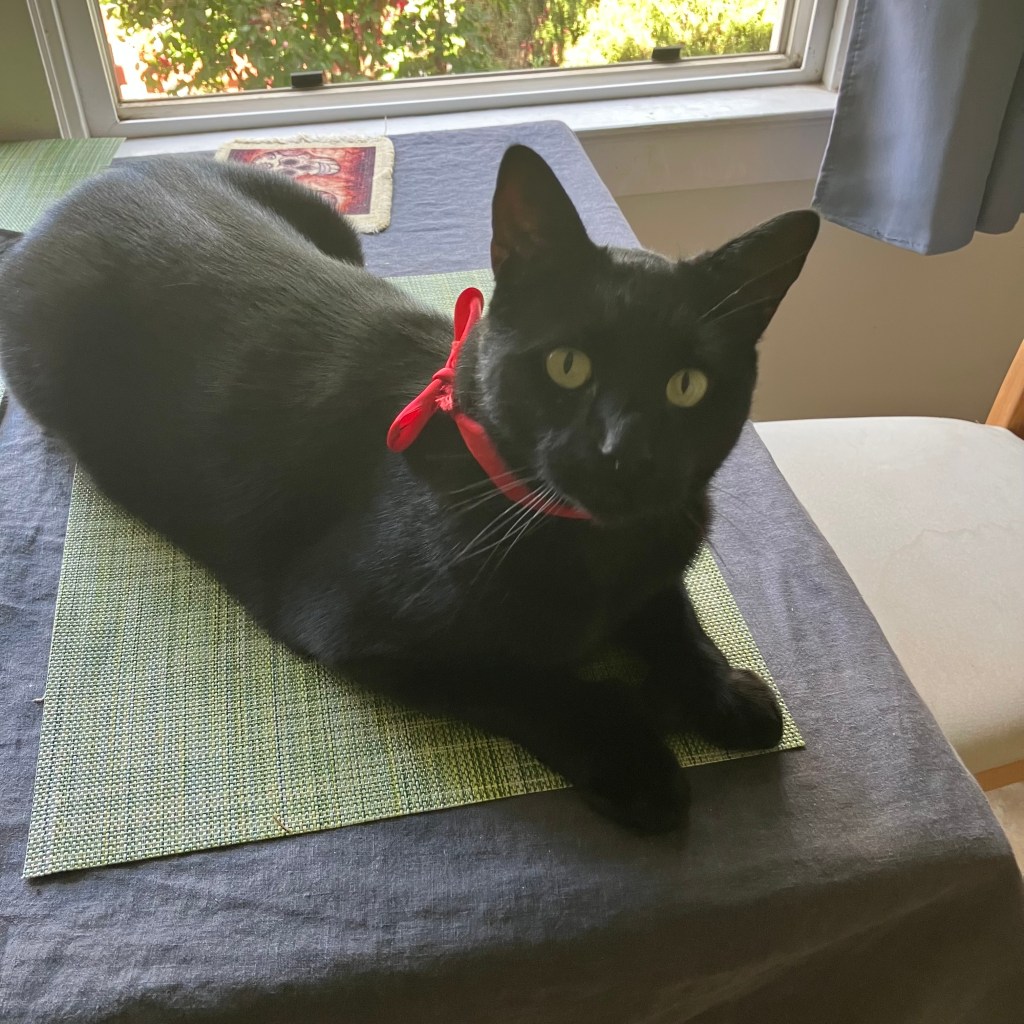

Mornings found me on the front stoop with a hot cup of coffee and a newspaper. One day a friendly cat with fur even blacker than the coffee strode up to me demanding to be petted. He was handsome, slender without looking sickly, and his front paws demanded a second and third look. It seemed like he was wearing mittens. He had what looked like smaller paws jutting out from his regular paws. On closer inspection, he had three extra toes on one paw, and two on the other, each additional cluster nestled into its own separate small paw. I was fascinated. I soon learned about polydactylism and the infamous “Hemingway Cats” of Key West, Florida.

I misgendered this cat, sadly, from the start. Everyone thought he was a she. I’m not sure why—maybe because male cats do not have the obvious penis that dogs do, but instead just a tiny nub tucked away beneath the lower belly fur. Regardless, she/he was demandingly friendly, adoring pets and strokes and chin and neck scratches from me, my neighbors, and anyone else who walked by. He had no collar or tag, but seemed quite clean—this is before I learned that cats naturally kept themselves clean—and I figured he belonged to someone who lived nearby. I was careful to wash my hands after petting him, having a life-long allergy to his kind.

I had never had a close relationship with a cat. They were fun and interesting creatures for sure, but I seldom lived with one in my home. My oldest sister—one of the Tracys—had one when I was a really little guy, but I don’t remember him well. Later, when my mom and I moved to Los Angeles to live with my new stepdad, we found he had a Manx named Kitty, who mainly lived in the garage and on the streets, but sometimes came inside. Her stubby tail, a trait of the breed, would wag when we’d pet her, but I was very careful to keep my affection to a minimum, as cat hair on the hands inevitably led to cat hair on my young face, and I would be red-eyed, itching, and wheezing for the next several hours.

Kitty had kittens once. Being unspayed and allowed to roam North Hollywood at will, it should have been no surprise. But one day, we discovered she had birthed four kittens underneath my stepfather’s workbench in the garage: an orange tabby, a black and white, a jet black, and a runt I can’t remember—who died within a couple of days. I cried for hours upon learning this news, but today I remember no details about the unfortunate little sister. The survivors though? They were cute as fuck.

I would have been about nine then, when my mom drove me to the local supermarket, Alpha Beta, on the corner of Burbank and Whitsett, with the three surviving kittens in a cardboard box and a sign that read “Free Kittens.” I put the box in a shopping cart and stood outside the store, alone, for hours. Someone scooped up the black and white almost immediately. Later, a kid about my age took the orange tabby and informed me he would go home and ask his parents if he could keep it. If they said no, would I still be here so he could bring it back? Sure, I said. I didn’t have a watch and I had no idea when my mom was coming back. The little black kitty remained.

Mom pulled up at sunset in the family’s ’77 Caprice Classic, and I approached to let her know that a kid was maybe going to come back with the orange kitten. “Get in the car, now!” she ordered. I scooped up the box with the remaining black kitten and we drove home, tires shrieking, burning rubber. She and my stepdad consented to let my stepbrother and me keep the black kitten, whom we named Sheba, as in Queen Of. Sheba was a gorgeous but skittish cat, who rarely came inside and seemed to enjoy the wild life with her mom—coming in and out of the square hole that my stepfather and I had roughly cut for her in the aluminum garage door.

And that was pretty much it, cat-wise, until I got married twenty years later. My ex-wife came with two beautiful cats: a gray named Mouse and a black named Emma. They were accustomed to outside life, but they lived with us indoors for a short time at our rental in Land Park, until we bought the house in River Park. When they were inside, my allergies bothered me a lot, so they were soon demoted to garage cats—with a door (again, one I sawed myself—this time with a proper cat flap and housing, not just a rude cutout)—and there they lived until they eventually died, came back to life, died again, and/or disappeared mysteriously. This is the way of outdoor cats.

Truth be told, that’s about the last I thought about cats. I had never willingly had one as a pet, believing myself so allergic that the concept was non-negotiable. Mouse was bitey and scratchy, and Emma was skittish and shy, so my relationship with them was at arm’s length—literally—at best. Emma was gone so long one time that we assumed she must have perished from either age or the neighborhood coyotes. We even held a little memorial service, painted a rock, and my sweet daughter Josie drew a picture of her that we taped above the remaining cat’s area in the garage. Emma surprised us several months later when she showed up clean and very well cared-for. Certainly, a well-meaning neighbor must have taken this ragtag old black kitty in, groomed her, taken her to the vet, and then—upon Emma’s first chance of escape—she came right back to her neglectful household. Eventually, she died for real, and we buried her in her previously fake grave.

Origin Story

Years later, a year after my divorce and move to the V Street fourplex, this friendly, black, many-toed little feline starting coming around my front door. I was fresh off of a rough breakup with a long-distance girlfriend of several months. I was a mess, as anyone who gets divorced after decades of marriage will tell you they are. (Hey, we try our best. We just want to love and be loved, and we make a lot of mistakes. It’s just the way it is.) I was in a very low place, but understand this: my low places are not as bad as others’ low places. I dodged the clinical depression bullet from which many in my family suffered, and my anxiety is more normal than acute. I tend to roll with life. I fuck up a lot, but never with ill intent, and my baseline is thankfully a happy/content one. This is where I was in October, 2019, when Salem came around asking for pets and lovins.

Our hangs became routine, and I eventually bought a little bag of cat treats and put them in a small Tupperware. I loved getting home from work to find him, if not waiting for me on my stoop, coming around within a few minutes, meowing and demanding pets and lovins. Once I started giving him treats, I knew I had a friend for life. It got to where I could shake the little container and he’d coming running at the sound of the rattle from the depths of the night to eat a little treat out of my hand.

Once I saw him stalking some prey near a Camphor in front of my neighbor’s house. It was cool to see, having not spent too much time around cats before that. Finally I spied the prey: a small gray mouse blending into the ground and the tree. Salem chased him around, but didn’t seem to want to eat him. He would bat him around, back and forth, the poor mouse looking petrified. Finally the mouse shot up the tree and I figured he would be safe then. But Salem leaped a few feet from the base of the tree, knocked the mouse back down, caught him, then carried him gently in his fangs into the neighbor’s yard. I don’t know exactly how the challenge ended, as I needed to get home, but it was fascinating to observe and film.

Salem. Why did we call him (or “her,” at the time, remember) Salem? I couldn’t say. My neighbor Penny owned a large Craftsman home, and by my count, four roommates lived with her: Rebecca, probably in her mid-30s; Rebecca’s son Tristan, a sweet kid of around 10 or 11; Rebecca’s boyfriend, a musician; and another guy named Tom. In total, five people lived in the somewhat dilapidated house, along with a couple of big German Shepherds.

I spent a fair amount of time on my front stoop back then, drinking coffee in the mornings, a cold beer in the evenings, and feeding Salem “her” snacks whenever she would come around. Rebecca and I would chit-chat sometimes, and eventually we were mainly talking about the cat. Rebecca and her son named her Salem. I didn’t know at the time that this was the warlock-turned-cat Salem Saberhagen from the comic and TV show “Sabrina the Teenage Witch,” but she was black and had so many toes, she seemed witchy. I don’t think any of us knew at the time that the fictional Salem was a male cat, so it was fitting that he turned out to be male later. But we’ll get to that.

Rebecca got to feeding Salem on the Craftman’s expansive front porch, and she put out a water dish for her too. It wasn’t clear that Salem belonged to anyone on the street, or anywhere close by. She was a bit skinny then, hungry, and starved for human affection. She was quite clean, despite apparently living outside full time, and more affectionate than almost any cat I’d ever met. I was delighted! I knew my allergies would never allow me to have a cat of my own, but this was the absolute perfect solution! I had no responsibility nor expense of cat ownership, but I had a friendly, clean, many-toed creature to greet me every day when I came home from work. Kind of a “stray-with-benefits.” I loved this cat so much, I was thinking I should probably talk to Rebecca about pitching in a bit for the food she was buying. I wanted some stakes here.

But after a few blissful, healing weeks, trouble arrived in paradise. Just as I was settling into my new kinda-pet-having situation, Rebecca began telling me about problems Salem was causing with a roommate. I’d met Tom once or twice, as Penny had invited me over to share a joint with them one day, long before Salem was in the picture. He was a big, taciturn guy, and I can’t say I especially liked or disliked him. However, he had apparently cut a permanent hole in his ground-floor flat for his own cat—although, according to Rebecca, his pet was a scaredy-cat who didn’t even venture outside anymore. Tom’s cat had her own food, water, and litter box within the small dwelling.

Well, Salem had sussed out this bounty of food and water and took to entering Tom’s flat in the wee hours, when all was quiet, in search of sustenance—while Tom’s cat hid under the bed. Salem has, deep in his DNA, a bitter hatred for every other cat who roams this earth. He has fierce incisors and sharper claws—and more of them—than should be legal. He loved nothing more than to fight—preferably to the death—any other cat he saw. Especially Tom’s little scaredy, who had an always-open door.

Apparently, Salem would sneak in at night, eat Scaredy’s food, then fight with her under, on, or in Tom’s bed. Then Tom would roar awake, yelling—and Salem would flee. Tom blamed Rebecca for all this, and Rebecca would anxiously tell me that they might not be able to “keep” Salem because Tom was bitching about these indignities constantly. I couldn’t believe this was a real issue. The man had a goddam permanent hole cut in his door with cat food on the other side of it, so why was he surprised that a stray had found her way in? Apparently, since Rebecca was feeding Salem on the porch, it was her fault. Rebecca said she had tried to get Salem to come inside at night—where there was no access to the ground floor flat—but the cat refused because of the German Shepherds who legitimately lived there. Rebecca would often come talk to me on my porch as I was petting Salem and relay how bad the situation was.

The anxiety was maddening. Finally I told her to simply stop feeding the cat. I would put some food outside for her, and she could wash her hands of Salem. Apparently this Tom guy was a real tyrant though, and she swore it wouldn’t solve the problem. I said the solution to the problem was him not having a hole cut in his door. If not Salem, some other creature was sure to find its way inside to bother him. Regardless, I argued, if Rebecca stopped feeding her and I started, Tom could come talk to me if he had a problem. I didn’t live with the guy, and I was unconcerned about which animals came inside his open door. But Rebecca seemed legitimately afraid.

Then, one fateful night, my heart broke when Rebecca texted me: “Hi, there was a big blow-up this morning with the roommate. I have no choice but to take the cat to Happy Tails tomorrow. Just wanted you to know that this would be Salem’s last evening on V Street…” I was stunned. I loved this cat so much. I didn’t understand this newest blow-up; I hadn’t thought it would come to this. I had just gone through a painful breakup with a woman—my first real girlfriend since my divorce—and Salem had quickly wormed her way into my heart and stayed there. I couldn’t imagine her going away because of some stupid, avoidable issue with the roommate.

What I didn’t know then—but I do now—is that animal shelters, especially high-end ones like Happy Tails in Sacramento, don’t take in healthy outdoor cats, except perhaps to spay or neuter them and send them back on their way. These cats are fending for themselves out in the world, and human problems do not require the intervention and resources of shelters. Rebecca and I had a lot of back-and-forth over text for the rest of the afternoon and early evening, with me imploring her to simply stop feeding Salem so she could personally be done with the issue. But apparently Tom was making everyone in the house’s lives miserable about the cat, and Rebecca saw the shelter as the only solution.

I was despondent. I had a concert to attend at Old Ironsides, to see some local bands with friends. I was pretty buzzed, walking home alone at 11:00 p.m. after a fun night taking my mind off Salem. But ten minutes into the walk, alcohol’s famous lowering of inhibitions—and encouragement of questionable snap decisions — pulled my phone from my pocket and had me texting Rebecca:

“I’m gonna take the cat to the vet tomorrow to see if she’s microchipped. If she’s not, I’m gonna microchip her to my name and address. Then I’ll license her to me with the city. Any problems with anyone in your household, please call or text or knock on my door. Thank you so much for taking care of her these last few weeks!”

It became crystal clear that negotiating with Rebecca was getting me nowhere. It was time to take decisive action. As I walked home, I knew I was about fifteen minutes away from grabbing Salem—who would surely come running when he heard me come in, looking for pets and treats—and welcoming him into my home. It would be the first time in my life that I owned a cat by my own choice.

Rebecca was still trying to negotiate, but I was halfway to drunk at this point and I would not be swayed. She replied, concerned that Salem would continue messing with the other cat, and letting me know that she would have to deal with the consequences if there continued to be problems. She was supportive in theory of me taking Salem full-time but seemed traumatized by Tom. I didn’t reply. When I arrived home, Salem came to my door as expected. I scooped him up into my arms and brought him inside to my apartment. He had been eyeballing it for weeks, trying half-heartedly to weasel in between my legs whenever I came home. He got his wish.

And there he was. In my home. I had no litter box, no cat food, no supplies, no nothing. I prayed to God I wouldn’t have an allergy attack, but so far petting him had not caused me any issues. I opened a can of tuna, spooned half into a bowl, and gave him a saucer of milk. He very gratefully consumed all of it. I have a giant L-shaped couch, and I folded up a small blanket in the crook of the L, petted him, and put him to bed. Only then, about 45 minutes after Rebecca’s pleas, did I respond, and I did so succinctly.

“It’s not your problem anymore. It’s my and Tom’s problem.” And then, “We’ll figure it out.” Rebecca was still worried, texting me that she had promised to take Salem to the shelter tomorrow, and now she didn’t know what to do. I replied, “No worries. I’m taking the day off tomorrow to deal with her. She’s my cat now. She’ll be indoors tonight. Tom and I can communicate about her tomorrow or whenever, and there are other neighbors who love her too.” Rebecca couldn’t let it go, though. “But how do we stop her from messing with Tom’s cat?” To which I replied, “Yep, that’s a thing that Tom and I will have to deal with.” And that was it. I think Rebecca realized that she was stuck between two stubborn men. Possession is nine-tenths of the law, as they say, and Salem was now inside my house. Salem and Tom would be my problem from now on. (This tale is far from over, but the Tom problem ended at this time. Salem slept inside at night from then on, and I never spoke to Tom again.)

Alcohol has been a complicated issue at times in my life, but this was an experience I absolutely credit to booze—bringing this amazing creature and me together. Had I been sober then, I’m sure I would have cried and belly-ached about it. Knowing me, I would have acquiesced to what seemed like the smoother path. Walking home buzzed from Old Ironsides that night, though, I credit the IPAs and whiskey gingers for giving me the courage to say, “Fuck this bullshit. It’s my cat now.” End of story. Well—beginning of story.

I was nervous that night, but somehow I eventually fell asleep, my bedroom being 30 feet or so from where Salem was curled up in the L of my couch. I prayed he wouldn’t shit or piss, especially on the couch. I woke up the next morning and crept into the living room. Salem was right where I left him, curled up and content as could be. I saw no evidence of shit or piss or anything amiss. He was so freaking cute: silky smooth black fur, yellow/green eyes, way too many toes, and he just loved being pet, especially on his face and head. I gave him a little more tuna, which he gobbled up greedily, and then I let him out the front door to go potty. I made coffee and started Googling how to check if a cat is microchipped, then made a vet appointment. After a half an hour I went out to my stoop and shook the little plastic container that held his treats and he came running, presumably all shitted and pissed out. I locked him in the apartment and drove to Petco for a litter box, a scooper, poop bags, cat food, a carrier, and some toys. He was perfectly fine when I returned, and now I felt like I could truly be a cat owner.

He took to the litter box immediately, and to this day—six years later—he has never pissed anywhere but the box. Damn, I was a real cat owner! I couldn’t believe it. All the bitching and moaning and sneezing and itching I’d done around cats over the years, and now this sleek, bad bitch was living in my home with me—by my own choice! I didn’t even have any plants at this point in my life. I bragged that I could shut my front door and take a trip for an indefinite amount of time, and there were no children, pets, or even plants to want for anything in my absence. It was liberating. But having been a parent for the previous 25-ish years, I truly did still seem to require some responsibility in my life. I didn’t choose the cat—but the Universal Cat Distribution System chose me. So there I was.

I called out of work and took Salem to the Front Street Animal Shelter the next day—a Friday. Thankfully, I had the whole weekend ahead of me to acclimate to being a cat owner, and for Salem to acclimate to being a person-owner. I had checked Craigslist, Nextdoor, and the Sacramento Bee to see if anyone had placed a lost cat ad, but I saw nothing. The shelter told me she wasn’t microchipped. OK—this was getting more real by the moment: she was mine.

I took her to the vet on Monday and found that she was an exceedingly healthy cat, about a year old. And by the way, the vet asked, was it very important to me that Salem be female, as I’d indicated on the intake form? Because “she” was absolutely not. The vet held him up to show me. “See?” I couldn’t really see anything, except what might have been a tiny nub deep underneath the black fur near his hind legs. I never looked too hard—I just took Rebecca’s word that Salem was a she. Salem, a boy cat? Fine by me!

The other interesting news was that he had already been neutered. What the hell? Where did this little creature come from? He was friendly, domesticated, not overly skinny—and neutered. Was this someone else’s cat? In those early days, I would have considered giving him back to someone, but did they really not wonder where he went at night? Over time, I talked to many neighbors in the area, and everyone knew him. Despite his slightly slender frame, a handful of neighbors occasionally fed him, but no one knew if he actually lived anywhere in particular.

Thinking back on this now, six years later, I’m sure he lived somewhere nearby. Just because he wasn’t microchipped didn’t mean he didn’t belong to someone. But even if he did, he was obviously a full-time outdoor cat, and that means he didn’t truly belong to anyone. And since he was shelter-bound, thanks to the neighbors, I believed then—and still do—that he was better off with me.

He graduated from the couch to sleeping in my bed, above the covers and on a little blanket at the foot, because I’m not a weirdo, and we quickly settled into a routine. I was working in an office full-time back then, just months before the Covid pandemic hit, so I’d let him out in the morning on my way to work, and call him back when I returned, about nine hours later. It put a cramp on my social life, as I was accustomed to following Jeff or Scott to Dive Bar, Republic, or Torch Club after work for a beer, and then who knew where the night would take us. But now I had a cat to feed, so there was a lot of, “OK, I’ll meet you guys there, I gotta go home and feed Salem first.”

I soon found out what every cat owner knows: feeding them is a big pain. I gave him a quarter cup of dry food every morning and a quarter cup at night, but he learned the routine very quickly and began walking back and forth across my head as I slept—beginning at about 5:00 a.m. every morning. This would not stand, so I invested in an automatic feeder.

I decided that for his age, activity level, and weight, he’d need approximately 5/8 of a cup of food per day, so I set the feeder accordingly—feeding him 1/8 cup at precisely four-hour-and-forty-eight-minute intervals. Every day at 11:00 p.m., 3:48 a.m., 8:36 a.m., 1:24 p.m., and 6:12 p.m., the feeder would make its little noise and drop a meager portion of kibble. Salem would come running. Sprinting.

The best thing about the feeder was that Salem didn’t see me as his food source—it came from the robot overlord. And since his food came at tight, regular intervals, he didn’t even bother the robot. He eventually learned to meander up to it within about twenty minutes of its output, and we were all much happier. He slept at the foot of my bed and never bothered me about food again.

The Couch Problem

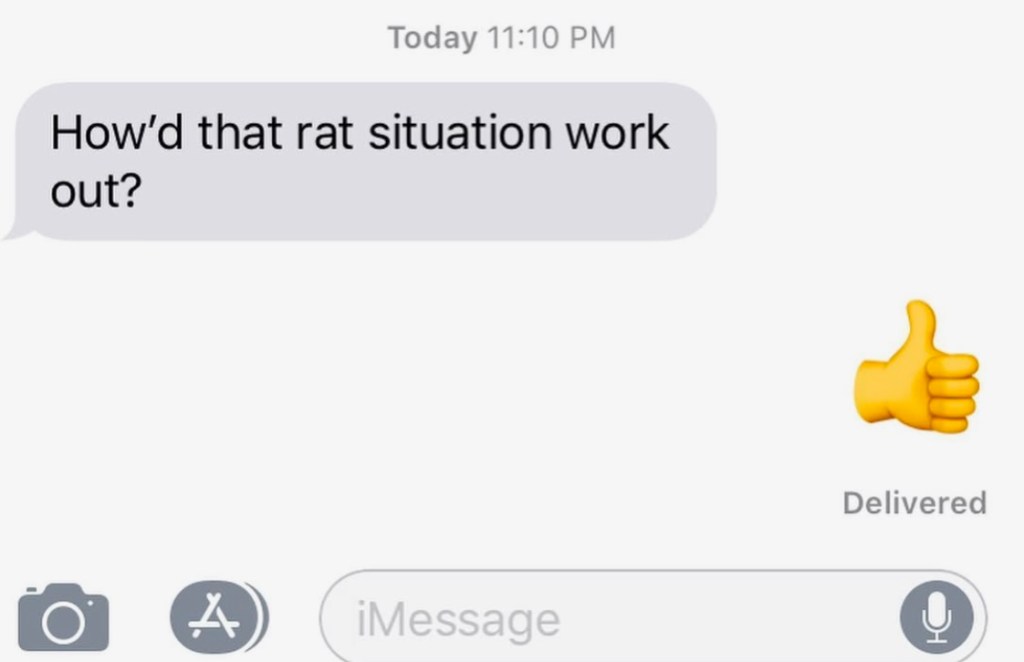

Salem had many adventures outside in those days, more than once bringing a live rat or mouse to the area around my front door. At that time, I never knew him to kill one—although I’m sure he did—I only ever witnessed him playing with them, to his utter delight and to the rodents’ terror. He would even walk around with the petrified creature gently held in his mouth, like his own baby, only to get bored, set it down, and resume chasing it. One poor, small rat was running round and round a large flower pot at the front of the fourplex, with Salem prowling either side. The rat would stick his little head out, see Salem, scurry to the other side, while Salem would do the same and chase him round and round again. Finally, I needed to bring the cat in for the night, so I implored the rat to stay still for a second so I could grab his aggressor. He obeyed, and Salem sadly came inside. The rat was gone in the morning.

I had my kids take care of Salem one night when I was out of town. I told them how to call for him at dusk, how to shake his little snack container, and I warned them it may take a while. Henry and Josie were about 20 and 17 at the time, and they witnessed some more rodent-chasing. Apparently Salem was chasing a rat outside my apartment door, and the kids were enjoying the show. But they were in a hurry to meet their aunt, so they opened the door to bring Salem inside for the night, feed him, and be on their way. Well, the rat ran in first. Salem followed, and the rat scurried under my huge L-shaped sofa, which is legitimately as big as two extra-long twin beds shoved together, with only about a 1.5-inch gap underneath it. Salem stalked the rat, running from one side of the sofa to the other. The poor creature was never going to come out—and the cat would never be able to reach it.

The kids were in a pickle. They needed to go meet their aunt, but they knew they couldn’t leave a live rat running around my apartment. Their first course of action was to lock Salem in the bedroom, wisely; the rat would never come out with a giant black cat head peering under the couch from every possible angle. With Salem locked away, however furious, the kids faced a new conundrum: how to get the rat out.

The couch was four feet deep by twelve feet long, in an L shape. I like to tell people it sleeps seventeen. When you sit in it, you sink so low and luxuriously you think your butt is going to scrape the ground. I tell people it’s a vortex—that they just need to go with it. Don’t fight the couch, I tell them. Let it take you. It’s your only option.

A rat hiding under my couch is like a flea hiding on a St. Bernard—you know it’s there, but good luck finding it. The kids cleverly decided to open the front door again, so the rat would have an exit plan. They found my broom, but believe it or not, not even a broom handle was long enough to reach the nether pockets of the undercouch. Even my pushbroom handle was angled too weirdly to force the rat from his hidey-hole in the inner L. Finally, they had the idea to duct tape two wooden spoons to a roll of cardboard wrapping paper to assemble the ultimate rat chaser-outer.

The plan worked. But during the crisis, they called their mom, as young adults do. “Um, we have a situation over at Dad’s.” My ex-wife, not unkindly, said something to the effect of “This is something that falls outside the range of a ‘me problem.’” And I understood completely. My kids knew I was down in L.A. hanging out with old friends, and they didn’t want to bother me. But their mom did not live in this apartment, was no fan of rats, and had no actionable insights for them. I applaud her non-reaction.

Again, the plan worked. The rat scurried out the door; the kids slammed it shut and triple-locked it, then let Salem out of the bedroom, laughing as he frantically began haunting the couch—stalking his murine prey, who, unbeknownst to him, had already vanished.

They finally called me later as well. I was in the middle of meeting my old friends Tony and Chad at the Formosa Cafe in Los Angeles, and I had no time for this nonsense. I trusted they would take care of the situation. If they didn’t, Salem surely would. I wasn’t super worried about it, but I could tell they were.

Later, after a crazy evening with my sixth-grade buddies, I remembered their call and shot them a text.

And that’s pretty much how the situation resolved itself. To this day my kids are bonded by their traumatic and heroic Salem vs. Rat adventure, while it barely moved my needle.

Salad Days

The cat had many adventures outside, most of which I knew nothing about. The poor fellow didn’t know this was all about to come to a screeching halt. But before I get to that, I want you to consider the life of this little black panther, patrolling the blocks around V and 18th Streets, climbing so high up the Camphor in the fourplex’s driveway that I had to go inside for fear of watching him fall. He never did. He would traverse the back and side fences of the neighboring homes like a tightrope walker. He routinely offered a dead rat or mouse on my doorstep, confirming that left to his own devices he would in fact kill a rodent. He chased squirrels and birds, and fought like hell with other cats. More than once, he came home filthy—covered with dirt, weeds, old leaves, and sometimes even blood from his scrapes with others of his species. I learned not to worry, as within an hour he was completely clean from self-grooming, his brilliant black coat shining and perfect.

Because he was such a rambler, I bought him some reflective breakaway collars, and ordered a tag that simply said “Salem” with my phone number on it. Safety first, right? I was surprised that he took to the collar so readily, and it looked really cute on him. I’ve known other cats that wrestle their way out of collars within minutes, even the non-breakaway kind.

He was beloved by everyone on the street. I never really saw Tom after the drama a few months back, but Rebecca and her son were always happy to see Salem on the street, petting him, and he responded as if he remembered their early care for him. Or maybe it was because he was just a big lovey boy. Probably both.

Those were the salad days. Just a few months before the Covid-19 pandemic, and I was a year into my new life living in Midtown. I walked or rode Jump Bikes everywhere, I had various romantic relationships and flings and things in-between, and now I had a cool-ass cat with 23 toes who would mostly come home when I called from the front stoop at 5:15 p.m. after returning from work, which was just a mile away. He would be in for the night then; I didn’t want him bothering Tom anymore. I’d feed him and hang out with him, and then often venture back out into the evening to see bands, hang out with friends, and get up to miscellaneous shenanigans and tomfoolery. Wandering home later in the evening, Salem would always be waiting for me, coming up to rub against my legs, give me some friendly meows, and ask for a treat.

Did you ever have a friend with drawstring window blinds and wonder why those blinds were always raised up about a foot above the sill, privacy be damned? That friend had a cat. You would have inevitably found one blind in his or her house that has been destroyed by their kitty wanting to do nothing more than simply scoot behind it so it could look out the window. Eventually, cat people learn, and they either keep their blinds raised by twelve inches, or they get shutters or curtains. I eventually got both, at this and later houses.

Most times when Salem returned home from his outside adventures he was, again, absolutely filthy, sometimes a bit bloody, sometimes missing a small patch of hair. My little guy was a fighter. He loved people, tolerated dogs, but seemed to treat every other cat as a mortal enemy. I’ll say it again: No matter how ragged he came home, he was always perfect and clean within an hour or so. Magical creatures, cats are.

Crash

About four months after the Universal Cat Distribution System brought Salem and me together, a day came that I’ll never forget. A Sunday morning in mid-to-late February, 2020, right before the pandemic, started as a glorious day; Salem and I woke up around 8:00 or so. I fed him, changed his litter box, and gave him fresh water. Eventually I made coffee, wandered out to my front stoop to find my newspaper, let Salem out, and sat down to enjoy the morning. I saw a squirrel run east down the sidewalk, past the neighbor’s fence and out of view. Salem darted after it. I muttered a half-hearted “Salem!” as if to say, “Leave the poor squirrel alone.” But I left the latter part unsaid, as there’s no telling a cat what to do. All in all, it was a normal, lovely, Sunday morning. A few minutes later, I heard odd, distressed cries that, I’m ashamed to say, I didn’t at first recognize. But after about the third one, I set my coffee cup and paper down to wander down the sidewalk to see what was up.

Salem was lying in the middle of the street, howling. I ran to him and could tell immediately he had been hit by a car. His body was twisted almost perpendicular to itself. The sadness and horror in my heart in that moment—mere seconds after enjoying such a pleasant, normal morning—is familiar to anyone who has experienced tragedy. Yes, even with a pet, it’s tragedy. Not as much as with a person, but more than probably anything else. My perfect, loving, unique, 23-toed buddy was a twisted wreck on the street, screaming. Instinct took over—fight, not flight or freeze, thankfully, maybe the result of raising children—so I scooped him into my arms and sprinted back to the house. I closed the screen door so he couldn’t run out again, if he was even able to do so.

I set him down on the floor to assess him, but he bolted through the apartment, down the hall, and hid straight under my bed. His back seemed to wiggle in the opposite direction from his front, like it was broken. I saw blood all over my arms and on the floor.

I’ve never written about this. Everyone who knows Salem and me knows the story of his car crash. I’ve spoken about the event many times, but never in this much detail. It’s hard for me to write. I’m tearing up, even as I pass through these paragraphs on multiple edits; I’m right back in the horror of that moment. I’ve been terrified for the mortal safety of one of my actual children just once, thankfully. My child survived, and thrives today. But this takes me right back there. You think you’re in a nightmare. It seems impossible the universe has put you and your loved ones in this situation.

I looked under the bed, but let him be. He was shrieking, panting, drooling. Blood spots dotted the apartment, trailing the path he ran. I was freaking out, but I knew I needed to take fast action. The vet on call at Salem’s usual clinic sent me to a 24-hour emergency animal hospital, who said to bring him right in. It killed me to pull him out from under the bed and put him in his carrier. He was crying, screaming, yowling, and I was afraid I’d break him in half. I was crying too.

We drove the 15 minutes to the emergency vet, and they rushed him back to their intake room. I stayed in the waiting room trying to hold back tears. I just couldn’t lose this little guy. My life had been turned upside down just a couple of years prior, when my marriage ended. After a crazy period adjusting to single life, and another serious relationship already begun and ended, Salem represented the unconditional love and stability I realized I needed. After years of coaching Little League, raising kids, parent-teacher conferences and field trips, and sleeping next to the same person for over two decades, I needed more than records, friends, and bar crawls to help me feel whole. Salem did that for me. He was the first pet I ever had who was just mine. I wanted him. I needed him. And he seemed to want and need me back. I loved him with my whole heart, truly. Not like my children, but a lot. More than I thought I would.

The vet called me in from the waiting room, and we had the talk. I don’t remember the medical terms she used, but essentially, Salem had a broken face and broken ribs—thank the kitty gods, not a broken back. They could fix him, but it wouldn’t be cheap. Still, as a young, healthy cat, he could be expected to make a full recovery. I didn’t blink at the figure she quoted: between six and seven thousand dollars. I simply handed over my credit card, said hi to him—cowering in his little pen—and thanked the kitty gods a second time that he was going to be OK.

I visited him in the kitty ICU each day for the next several days. Aimless at home without him, I wandered into the street to where the crash occurred. There was his little breakaway collar with the “Salem” tag. I gathered it up, tossed the collar, but kept the tag. It was almost too much to bear—to look at that little piece of metal and think of how diligently it dangled from his neck, that I had so dutifully procured for his safety, and that he so obediently wore—for exactly one day.

When they let me bring him home, he was missing his top left incisor—he learned to live without it—and they had shaved him, out of necessity, in some absolutely crazy ways. Puffy legs, skinny neck—he was not ready to be a Calendar Cat. I had to feed him intravenously for a couple of weeks. He was a little weak, but overall he had the same loving personality, and he was back to his old self before long. With one exception: he wasn’t allowed outside anymore.

I felt badly about that, and I still do, all these years later. But I can’t go through this again. When he was an outdoor cat, I always knew—in the back of my mind—that I could lose him someday. The thought brought tears to my eyes, but I knew I needed to face facts. Look, he’s a cat. He spends his days outdoors. One day he may just never come home, or I may find him dead, or someone may tell me they saw a dead black cat with 23 toes. I didn’t want any of that to happen, but part of my heart was steeled to the possibility. What I didn’t consider was the immense agony he could go through, followed by the “We can save him, but give us seven thousand dollars” conversation.

I didn’t hesitate to pay. As a newly divorced guy paying for college for one kid, and alimony, I wasn’t exactly rolling in dough. But I didn’t think twice about saving my kitty’s life. And I was disciplined, paying the bill off over the next year. But after that, I would look at Salem from time to time—usually just after I had made a payment to my credit card—right into his devilish yellow eyes, and say, “You are NEVER going outside again. NEVER!”

A New Life

Salem’s quarantine started about one month before the rest of the world’s; fortunately, he only had a few short weeks of being cooped up alone in the apartment before he had me to keep him company, working from home full-time starting in March of 2020. Then we were cooped up together, except eventually I was allowed to go back outside and he wasn’t.

Salem mainly took to his new situation without issue, although he would stare longingly out the window at his old life. He did become more aggressive, though. The outside world had allowed him to roam, climb, scratch, claw, fight, and then come home tired and ready for cuddles. After his recovery and confinement, no matter how much I played with him to try to get his energy out, he still very much wanted to scratch something—and that something tended to be me. It may have been out of guilt, but I kind of let him do it. He is the type of cat who loves pets and cuddles, but you have to do it just right. In the first few months of his indoor life, he would go hard on my forearms while I pet him and played with him. Some of it I invited, knowing my own cat well enough to understand that petting and scratching the top of his head and face was great—but if you moved down to his neck, chest, or belly, he’d try to trap you like a big rat: biting, scratching, and bunny-kicking.

I thought it was cute, and maybe I thought it was a kind of penance for imprisoning him, until one day—like someone in an abusive relationship—it took an outsider to say something for me to become alarmed. A lifelong blood donor, when I went for my next appointment, the woman checking me in took one look at my gnarled, slashed-up arms and said, “Those look infected. We can’t take your blood.” So after that, I played with him in safer ways.

Still, to this day, I caution visitors about him. I try to relay the specific way he likes to be pet, but they don’t always listen, and invariably they’ll veer too much toward his neck as he starts clawing them gently. I warn them, I really do. “You shouldn’t do that. He’s going to get you.” “Oh, it’s fine,” they always say, “It’s cute!” And then he goes in for the kill, and they end up with three puncture wounds on their forearm (remember the missing incisor) and a long scratch that requires a Band-Aid and Neosporin. I always keep plenty of both around.

The cat is incorrigible. He truly is. His veterinary clinic strongly urged me to give him a sedative before any routine visit, because he so hates the poking and prodding—despite them being the nicest, gentlest people, who deal only with cats at their facility. He does nothing but scream and howl and fight during checkups. It goes without saying that he won’t let me trim his claws—not a single one of the 23—despite the special scissors I bought. So I take him to a groomer for this purpose only—screw the grooming; he takes care of that himself—and only Rachel can handle him. If she isn’t working that day, I turn around and go home. Rachel is a living saint walking among mortals. Understand though: Salem does not behave for Rachel. But she can handle him, and she seems to enjoy seeing him, despite him being such a pain in the ass.

Like a good pet owner, I gave him Revolution heartworm and flea medication once a month. This required me to pin him between my thighs and make a feeble attempt at parting the impenetrable fur behind his shoulder blades, to squirt the medication directly onto his bare skin. I messed it up often, but even when I did it correctly, he would fight to find a way to gnaw at that impossible spot on his back—where he wasn’t supposed to be able to reach—to bore a perfect three-quarter-inch bare patch in his fur. Then he would puke from ingesting the medication. So guess what? I saved myself money and him aggravation by stopping the medication altogether. So far, no heartworm or fleas.

One day, a few months after the accident, I saw a Missing Cat sign stapled to a Sycamore tree directly in front of my apartment. The photo looked exactly like Salem! I examined the flyer, and saw that the pictured cat disappeared just a few days prior. I knew it couldn’t have been Salem, but was it a sibling? Could the owners have a clue about Salem’s origins? I decided not to contact them. I didn’t want to invite any complications that could even potentially lead to controversy about Salem’s ownership. The biggest problem with the sign was that it was posted directly in front of my apartment’s big living room window, where Salem spent a good portion of his day. Anyone walking by would see the sign on their left, and an identical cat on their right, staring at them, as if saying, “Please, call that number!” So I tore down the sign. Not all of them, just the one on the Sycamore outside my window. Who staples a sign to a tree, anyway? That’s what telephone poles are for.

We moved to a new house in the fall of 2020, after being together a little over a year. The new place was only two blocks away, rougher around the edges than the apartment, but it was an actual house with a front yard, back yard, garage, laundry/litter box room, and two whole bedrooms, one of which quickly became my full-time work-from-home office. There were a *lot* more windows for Salem to look out of, but the janky state of the screens—and lack of screens in a couple of cases—made me very nervous. However, I had great landlords who ordered me new screens on request, and I found a way to secure the rest of them. Or so I thought.

Escape

I lived in that house on 20th Street for about five years, and Salem escaped for extended periods exactly two times. He sensed when new people were visiting, and new people weren’t as vigilant about closing doors as Dad was. He also knew when my arms were full, carrying something heavy to the back yard. He escaped once that way, slipping out the back door from the laundry/litter box room when I was otherwise engaged with what I was carrying and struggling to get out the door. He crept behind the dryer like a ninja—I had no idea he was even in the laundry room—and when I set my bag of soil down to open the door and then reach back for my load, he bolted.

Fortunately, this freaked us both out equally. As soon as he dashed, I dashed as well. He ran behind a Yew Pine; I stood my ground. He slinked into some Rosemary; I called to him. He emerged from the bush, looking panicked, low to the ground, and I scooped him up. There’s a special method of grabbing a cat that you are desperate to keep hold of and get inside. The method is this:

1. Grab any part of the torso as fast as humanly possible.

2. Gather the skin in a vice-like grip.

3. Lift, and run inside.

That’s it. We had a good conversation after this, about how I didn’t want him to roam the neighborhood and get hit by a car again.

A few months later, some friends and I returned to the house after a night of rabble-rousing and trouble-making. We had bumped into a cousin of mine while out on the town, and the crew decided to return to the 20th Street house, as I wanted to show my cousin the new place and have her meet Salem. Well, we returned to an empty house. It was the time of year to leave the air conditioning off and go with open windows at night, to which I had responsibly seen before the evening’s events began. But Salem was nowhere to be found. My heart raced in my inebriated chest, and I noticed a sliver of an opening in the screen of my bedroom window. Damn, I hadn’t secured it well enough, and Salem finally found his escape. The entire crew ran out into the back yard, as I grabbed a can of tuna on the way.

Tuna is crack to cats; even the sound of a can opener drives Salem wild, even if it’s just Garbanzo beans. “Buddy, it’s just beans! You wouldn’t even like them!” “But Dad,” I can hear him say inside my mind, “Usually when you use the can opener thingy and I hear the sound of a tin lid popping off a can, that means tuna, and I LOVE tuna!!!”

We all called to him for a couple of minutes, and I made sure the sound of the can opener on the tuna tin was well-amplified in the back yard. It wasn’t long until a bedraggled Salem emerged over the back fence, through the Camellia, along the weedy, dead grass growing up from the other side of the fence, looking like a crackhead stumbling into a 7-Eleven at 1:00 a.m. looking for a Mountain Dew. He had an actual weed hanging from his face, foxtails on his back, and he was covered in dirt. I used the three-step method to get him into the house, rewarded him with the tuna for coming home, and promptly closed the offending window until I could fix the screen the next day.

The most serious escape happened a couple of years after that. I had just started seeing a really nice woman, and after a night out having fun and drinking with other friends, including her best friend and also her sister, we all came back to my 20th Street house for, yes, more drinks. Her sister was really nice. It was the first night we had met, and of course I wanted to make a good impression. Everyone oohed and aahed over Salem, as they always do, and I stressed the importance of closing doors and being aware of his whereabouts. I think.

The back yard at the 20th Street house was a good hang, with a fire table and a couple of Adirondack chairs. I had made Moscow Mules for everyone, and some of us were chilling back there, when I heard the sister at the back door say “Oh, oops.” My girlfriend’s ears perked up and she ran over. “Um, Chip, Salem got out.” “WHAT?!” I shrieked. I ran over to the door, and the sister said, “I think he ran that way.”

I frantically scurried through the back yard, behind the Rosemary bushes and the Yew Pine. Behind the Pittosporum, the Trumpetvine and the Acanthus. He was nowhere to be found. “Salem!” “Saaaaallllllem!” “SAAAAALEM!” I ran to get the can of tuna, and opened it loudly and exaggeratedly. “Salem!” My calls turned to a whimper in my drunken state. “Salem… Salem, sniff, Salem!” I was literally crying at this point. “Saaaalemmmm…,” trailing off, lamenting my long lost pet, who would surely never return. (It had been about 10 minutes.) I had scoured the yard with flashlight and tuna can in hand, getting covered in leaves and dirt. Eventually I sat on the back steps with the door open, hoping he would return but pretty sure he wouldn’t. Everyone went inside, a little freaked out by the drama and the crying. My girlfriend, to her credit, was calm and cool and sat with me for a while, assuring me that he’d come back. He was just off exploring, she reasoned. He knew his way home.

“You don’t understand,” I sobbed. “Last time he was out this long he got hit by a car. 21st Street is just over there, and he might get killed,” as I wept more loudly, punctuated by desperate cries of “SAAALEMMM!” I knew her sister felt badly; I didn’t want her to, but I was fixated on my cat, my buddy, my BFF who—let’s be real—had seen me through a handful of romantic partners by this point. Eventually my girlfriend let me be alone in my grief, saying goodnight to her sister and her friend. I rallied for the goodbyes, assuring them that I knew Salem would be home soon, not wanting the sister to be upset, even though I was certain he was already roadkill on 21st Street.

About an hour after the escape, when my girlfriend and I were alone in the house—she still giving me my drunken, grief-stricken distance—there he was. “Meow,” he said as he approached from under the orange tree. The patented quick-dash and vice-grip clutch got him into my possession, then into the house with the back door double-locked. I dropped to the floor, petting him, telling him how worried I was and how happy I was that he had returned. I gave him some of the promised tuna, then turned in, relieved.

Am I proud of my behavior that night? No. Do I one hundred percent understand my behavior that night? Yes. The girlfriend and I eventually went our separate ways—unrelated to the great escape—but Salem is still with me.

Today

Of course I know I will lose Salem someday. Hopefully to natural causes many years from now. Whether it’s a car crash today or old age in 10 to 15 years, it will devastate me; yet I will get through it. I was there for the family Labrador, Benny’s, last breath at the veterinarian. It was heartbreaking, but we all made it through. We lost my daughter’s beloved Mr. Moon, a dashing tuxedo cat, at the vet as well, as his illness and distress was untenable. The whole family was there for most of the procedure, crying and supporting our beautiful Josie, until she said goodbye to Moonie’s sweet, lifeless body, by herself. It will break me when Salem someday goes—which is partially why I write this, to ensure I remember every detail about his sweet little life—but I’ll survive. What I can’t handle is watching him go through another devastating injury, and then me being handed another vet bill I can’t afford. So Salem, for now, stays indoors.

One of my latest hobbies has been speaking at Moth-style storytelling events, and I recently told the story of how Salem became mine, ending with the first night he spent in my V Street apartment, rescued from Rebecca and Tom next door. I had only eight short minutes to tell that story. If you’ve read this far, it’s taken you much longer than that. Salem and I are now in our third house together, a home I legitimately own. He has yet to escape from this place, but I’ve actually contemplated letting him explore, off-leash, the back yard a bit. Of course, he knows no property boundaries, so we’ll see if I’m brave enough to let him roam. Likely, I’m not.

To finish our story, for now, in the summer of 2025, almost six years since we’ve been together, I’ll leave you with this. I won’t be dramatic and tell you that Salem saved my life. My life is in good shape, with or without a pet. I won’t tell you that he actually adopted me, rather than the other way around. We all know it’s the Universal Cat Distribution System that chooses cats and humans, regardless of the designs of either. I will say that I love this cat as hard as a person can love a creature, without being weird about it. He is my familiar, my daemon; we understand each other. In a way we are a part of each other. We respect each others’ space and boundaries, and occasionally get in one another’s way. I’ll soon be spending more time at the office—away from home more than either of us is used to. Salem will deal with it. He knows how to entertain himself. Well—he knows how to nap. He knows where he lives. He knows who he is. He is patient.

He knows I will always come home to him.

Leave a comment